Introduction

Overcommitment (promising more than one can do) is common in every industry. Overcommitment can be positive and cause people to stretch and grow. It can also lead to embarrassment, disaster and financial loss. Given that there is a range of outcomes, great project teams are very careful when making commitments.

There are many reasons that people overcommit. These include:

- Single focus: No other options are considered. Just say “Yes,” because we have to, always.

- Fact free: No data are used to evaluate the amount of overcommitment or communicate the risk of overcommitting.

- Conscious: Both parties agree to the risk of overcommitting and develop mitigation actions to reduce the impact.

- Psychological: One or both sides have a desire to punish, control, feel needed, or appease.

One common trait of individuals and teams that routinely overcommit is that no other options are considered. If the customer or big boss requests A, then A is committed to, whether it can be done or not. No further exploration or discussion is pursued. There is one request and one answer.

The approach of just saying “Yes” is probably the most common reason teams get into trouble. It is deemed easier and safer to lead the requester astray in the moment than engage in discussion. The concern is that a discussion might lead to conflict, and some people will avoid even potential conflict at any cost.

Individuals and teams that successfully avoid chronic overcommitment explore far more options before committing. They use data to understand their capacity and know what they can and cannot commit to. There is one request with numerous achievable options considered, each one with known risk.

Below are some questions to help you come up with other approaches to commitment and negotiation. There is no one approach that will work every time, and practice will be essential to make them work. The goal is not to eliminate overcommitment; this may be impossible. The goal is to improve your batting average and the degree of overcommitment.

Committing and overcommitting – individuals and teams

1. When you or your team receive a work request, do you:

- just say “Yes” to appease the requester in the moment?

- ask questions to understand the larger context and details of the request?

- ask the requester for the latest date they need a reply so that you know how much time you have to evaluate the request?

- ask about potential future requests so that you have more time to react next time?

2. When you respond to a work request, do you:

- just say “Yes” and hope it works out — or assume you can ask for forgiveness later?

- provide achievable options for them to consider? For example:

- offer a cheaper and quicker solution to get them started.

- offer a solution with an achievable schedule, not necessarily the date they wanted.

- suggest a solution provided in increments based on achievable dates.

- suggest a deluxe version, which costs more, but has additional features or scope they would like.*

- Provide data and details (e.g., labor, materials, availability, and risks) to substantiate your options so that they know you are credible.

- Suggest who is a better choice for the work if you are not a good fit.

*Consider this option if you sell stuff to customers for money.

3. When you overcommit to a work request, are you overcommitting because you:

- do not have good estimate and capacity data before agreeing?

- forget to use the data you have?

- do not assess the risks to you and the requester of overcommitting?

- are afraid to mention any of the data you have to the requester? (Ask yourself, “What is the worst that would happen if you shared the information?”)

- like overcommitting. It does something positive for you.

4. When there is disagreement between you and the requester (e.g., you can deliver by June, but they want April), do you:

- just say “Yes,” and hope it works out?

- understand the larger need they are trying to satisfy by the request (see Negotiation Example below).

- assess, communicate, and get agreement on the risks?

- communicate data and options to the requester with your whole team with you (in-person or virtually), so that this position is not seen as just one person’s opinion?

- say “No” to protect your integrity and their success?

The last option (saying “No”) is obviously risky to your employment. If you believe you are capable of the request, but not in the timeframe desired, then use the questions above to explore other options. If you have exhausted absolutely all options, then hunker down, communicate the risks, and refine your approach next time.

Presenting options

There is a skill to presenting options. Consider these steps:

- Present 3-5 achievable options. With each option, state the effort, duration, risk and assumptions.

- STOP TALKING and push the ball into their court.

- Answer questions but don’t offer better and better deals! Have the other side absorb the reality. If they push back, assess and communicate risk.

- Don’t assume this will be an easy discussion.

- Remember, they want the unvarnished truth and dependable deadlines – remind them!

- Later: remind them what was agreed to.

- Manage all changes. For each change, communicate the impact to estimates and risks.

Negotiation Example

One useful negotiating approach comes from the book “Getting to Yes” [1]. The basic premise is to assume that the position taken by each side (e.g., a June deadline or October deadline) is just one position of many that could have been selected to serve each side’s interest (e.g., time to do a quality job and the need to generate cash flow).

This negotiation approach includes conducting a joint brainstorming session with the other side on possible alternative positions to improve the final solution and each side’s ownership of it.

Below is one example. Practice will be essential to make this work for you.

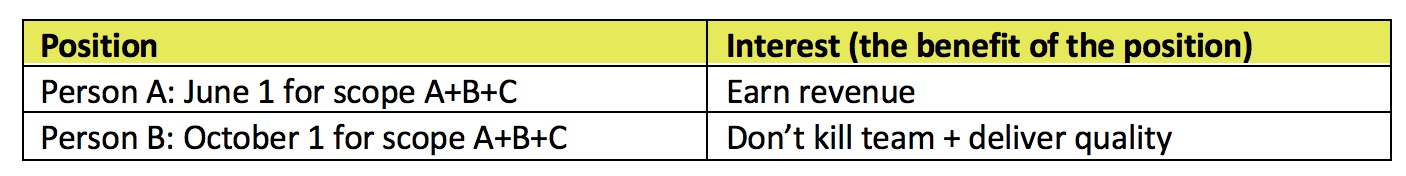

Step 1. State the positions of each side.

For example, before the negotiation, Person A wants a June 1 deadline for project scope A+B+C, and Person B wants October 1. These are obviously not compatible.

Step 2. Understand the interests of both sides (the primary benefit of the position taken).

Both sides state the benefit they are seeking from their position. Person A chose his or her position (e.g., June) to earn revenue, and Person B chose their position (e.g., October) to avoid killing the project team from overwork and to be able to deliver a higher quality product.

Step 3: Brainstorm options to achieve interests.

Brainstorm five to 15 options (new candidate positions) to achieve the interests of earning revenue, not killing the team, and delivering a quality solution. For example:

- Deliver scope A in June for some revenue

- Deliver A in June, B in July, C in October

- Deliver A+B in June with one extra resource

- Deliver A+B+C in June with two extra resources

- Add C to the existing system for June and deliver A+B in July

- Delay project D+E that is pulling existing resources from A+B+C and deliver June 15

- Use the previous option with external resources to test A early while B+C are being built

Step 4: Select a few achievable options to communicate.

The point is, the original positions were just one way to communicate the interest of each side. The negotiation process puts those aside and develops new options with the involvement of both sides.

Summary

There are more options than “Yes.” Researching options and practice are essential.

—————

Please feel to contact us if you need help in with planning, estimation and resolving commitment issues.

[Forward this email to your boss! Subject: Here’s a cool tip for you] Quick Link.Reference

[1] Getting to Yes, Roger Fisher and William Ury, Penguin Books, NY, NY.

The Process Group helps you improve your organization's capability to routinely meet deadlines and delivery quality expectations. We are certified CMMI appraisers / trainers and Certified Scrum Masters.

The Process Group helps you improve your organization's capability to routinely meet deadlines and delivery quality expectations. We are certified CMMI appraisers / trainers and Certified Scrum Masters.